Bodegas de la Riva

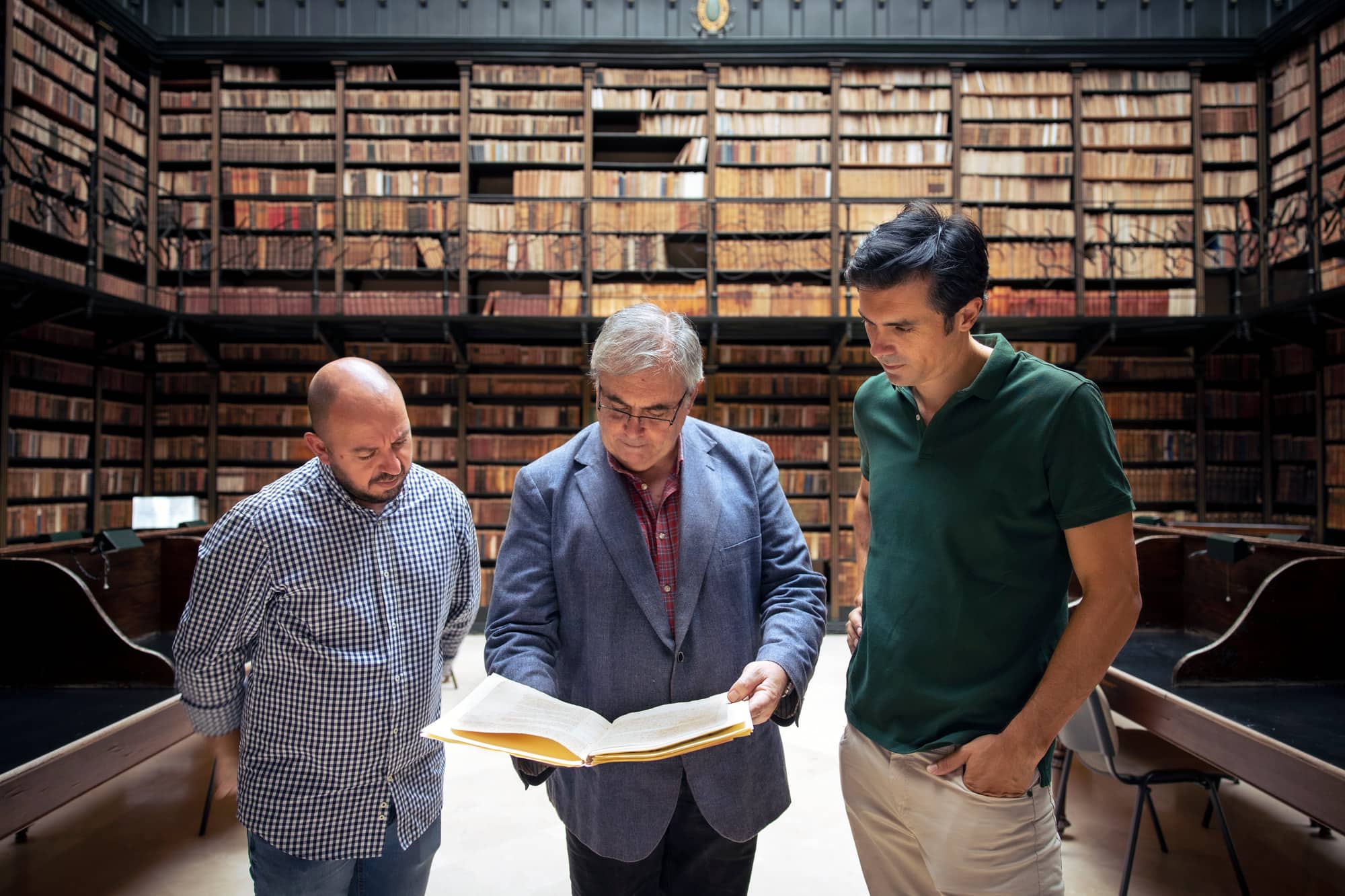

Ramiro Ibañez and Willy Pérez are hard at work. These two Jerez natives are moving. Writing. Studying. Teaching. Preaching. Making Music. And reinterpreting the history and the present of this legendary, yet often misunderstood, region in southern Spain. One part of this project of reinterpretation is a book: Los Sobrinos de Haurie. Los Sobrinos de Haurie is unique in its focus on the development of the complex methods of wine production in the area in the 19th century, and Ramiro and Willy are committed to documenting the intricacies and complexities of winegrowing, winemaking, and wine aging in Jerez and Sanlúcar in this poorly understood period. The second half of the 19th century was an era of dynamic innovation in Jerez and Sanlúcar, seeing the proliferation of Palomino, the development of the solera alongside the endurance of static aging processes, and the gradual invention of the systems of Sherry classification. Their archival and historical work revives and illuminates the complexity of viticulture in El Marco de Jerez, tracing the interrelations of soil, pago (the ancient, well-mapped vineyard areas of Jerez planted on the area’s signature varied Albariza soils), grape, and aging methods over the long history of the region’s wine.

The other half of this project is the rejuvenation of an historic bodega: M. Antonio de la Riva. To understand why Willy and Ramiro would want to revive an old name from Sherry’s past, it is important to understand their perspective on the history of Jerez, and the current situation of Jerez wine today.

As they tell the story, the Golden Age of Sherry simplified and eventually nearly replaced old vineyard-focused traditions with wines made according to a house style, favoring extensive flor-influence and fortification. The complexity of the relationship between pagos, aging styles, and finished wines was reduced, and something was lost. A part of this story is economic, connected to the broader history of Spain: the new model of industrial agriculture, house styles, and market monopolization by RUMASA stabilized the viticultural economy of Jerez in the 1960s (after the crises of phylloxera and civil war earlier in the century), but fortunes turned south in the 1970s as demand for sherry declined. Simultaneously, quality decreased, as the larger scale winemaking of the period sought standardization even at the expense of tradition and sense of place. Eventually, RUMASA’s dissolution in 1983 led to the bankruptcy of numerous old bodegas in Jerez. The remaining estates, large and small, have struggled to recover – even as old vineyard land has been replanted to other crops and storied botas and soleras have been left untouched for years.

Ramiro and Willy met in the mid-2000s while studying oenology Universidad Puerto Real. From there, Ramiro went on to spend several years as the head winemaker at the local co-op, an experience he holds in high regard as it allowed him to taste the wines and grapes from the various pagos around Sanlúcar and Jerez de la Frontera. This exposure gave him a special insight into the relationship between the grape vines and the many varieties of albariza. Contrary to current trends, Ramiro came to understand that the variety of terroirs and expressions of place and soil is itself the real source of Jerez’s long and successful viticultural history. After several consulting gigs, Ramiro started his own project, Cota 45, focusing on unfortified wines from pagos across the region.

From university, Willy returned to work at the bodega founded by his father Luis Pérez, professor of oenology at the university of Cadiz and an ardent traditionalist who had served as the head winemaker at the storied Bodega Domecq. Willy recalls that his father reached his limit with the industrialization of Sherry when Domecq abandoned the traditional asoleo (sun-drying) method, and in 2002 he founded Bodega Luis Pérez, where he and his son have focused on forgotten grape varieties and old-style, unfortified wines.

Part of a small new wave of young producers in Jerez, Ramiro and Willy reconnected in 2016 to start the de la Riva project and begin work on their tome on the history of the Jerez region. The bodega and the book fit together in their quest to return to the pagos and to revive the complex winemaking heritage of the region. In their writing, their winemaking collaborations (with each other, with other small producers, and with the region’s storied grand bodegas) and their independent projects, they are outspoken on the importance of careful work in the vineyard, and the intricate variations between pagos that allow for the production of high quality, vineyard-specific wines of individual character. If these ancient vineyards are allowed to speak for themselves, they argue, rather than being silenced by stylistic interventions or blended into standardized products, Willy and Ramiro are confident that the wider world of wine will want to listen.

Enter the revival of M. Antonio de la Riva. The M. Antonio de la Riva name has its own longer story. The original bodega was founded in the late 1700s, and already had a reputation for good wines when it was purchased by Manuel Antonio de la Riva in 1838. Located right across the street from the venerable Lustau, De La Riva was known for high quality sherries, old soleras, and holdings in the Pago Macharnudo until the early 1970s. The bodega and its wines were greatly admired by Jerezanos, and Willy and Ramiro noted that the wines always had a connection to the land. In the early ‘70s, M.A. de la Riva was sold to Domecq, who slowly dissolved the brand. When Willy and Ramiro were recently able to purchase a few rows in the Pago Macharnudo they decided to revive the long-admired De La Riva name in honor of its connection to the storied Macharnudo vineyard and in tribute to the traditional wines of its past. Ramiro and Willy, with inspiration from this ancient estate (whose wines they tasted in researching for their book), want to remake the reputation of contemporary sherry, reorienting towards specific vineyards and soil types, rather than cellar procedures or processes – embracing the complexity of Sherry’s past, and reinterpreting its future.

With these broad goals, Willy and Ramiro are open to bottling all kinds of traditionally made wines from El Marco de Jerez under the M.A. de la Riva label. Thus far, they have bottled their own unfortified wine from the plot they own in Macharnudo: De la Riva Macharnudo Vino de Pasto a wine aged under flor and made in the style of the 19th century. They have also contracted a solera of manzanilla from Bodega del Rio in Sanlucar, bottling the wine as De la Riva Manzanilla Fina Miraflores Baja. This contract is a sort of adoption, allowing Willy and Ramiro to take control of the maintenance and bottling of the wines from an established solera. To refresh the solera, Willy and Ramiro carefully select and source new wines and continue its steady, generational development. The pair also source and bottle wine from ancient botas of defunct bodegas: De la Riva “La Riva” Pedro Ximénez Viejisimo San José is from one of only three botas from the extinct Bodega M. Garcia Monge de Sanlúcar de Barrameda. And, finally, they purchased and recovered, a small, old Manzanilla solera, bottling the most characterful botas as De la Riva “La Riva” Manzanilla Pasada Balbaína Alta, and intending to allow the remainder to develop towards Amontillado.